Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

February 6 – 9, 2025

FABIO LUISI conducts

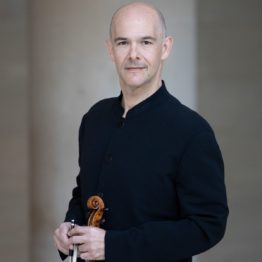

ALEXANDER KERR violin

RAVEN CHACON Inscription for Orchestra | World Premiere

BRUCH Violin Concerto

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 5

No other symphony has such instant recognition as Beethoven’s Fifth. Rising from its four powerful opening chords, it follows a euphoric path from tragedy to triumph, from darkness into the light, uplifting your spirits on the journey. Fabio Luisi also leads the DSO and Concertmaster Alexander Kerr in Bruch’s romantic Violin Concerto, once described as “rich and seductive.” Opening the concert is the world premiere of Pulitzer Prize-winning Native American composer, Raven Chacon’s first major work for orchestra. Discovered by Fabio Luisi, this promises to be a grand event in our community and for the Dallas Symphony family.

Join us for a special pre-concert talk with Assistant Conductor Shira Samuels-Shragg (Marena & Roger Gault Chair)! The talks will take place from Horchow Hall starting at 6:30pm on Thursday, Friday and Saturday and 2:00pm on Sunday.

Our Dallas Symphony Young Professionals will be in attendance to this performance on February 7, 2025. Learn more about how to become involved in DSO YP here!

You may also be interested in

Program Notes

by René Spencer Saller

You might remember this composer’s name from his Pulitzer Prize–winning work Voiceless Mass, an arresting collusion of pipe organ, chamber orchestra and strategic silence. Devastating in its restraint, Voiceless Mass proposes a paradox: how to express the collective sorrow of an indigenous people who have been oppressed, exploited, erased and silenced by the Catholic Church. Like many of Chacon’s compositions, Voiceless Mass is site specific, inspired by the performance setting — a cathedral in Wisconsin — and its many contextual meanings. Voiceless Mass, he explains, “considers the spaces in which we gather, the history of access of these spaces, and the land upon which these buildings sit.”

Other selections from Chacon’s catalogue are scored for even stranger assortments of instruments. In the minds of most listeners, some of these noise-producing objects don’t qualify as musical instruments at all. Chacon has scored works for firearms and the foghorns of three docked ships. He makes ambient recordings of the natural world and turns them into unfamiliar sonorities. He invites us to re-imagine our aural environment, to question our own assumptions.

As both a visual artist and an active musician, Chacon resists traditional dichotomies such as high vs. low, tonal vs. atonal, music vs. noise, embracing a more inclusive, or less hierarchical, harmonic language. While composing for firearms (Report) and foghorns (Chorale), he was obliged to create new notational systems that would be legible to the nonmusician performers — volunteer shooters and professional sea captains, respectively. Some of Chacon’s scores are literal works of art that have been displayed in the Whitney Museum of American Art and in many prominent international exhibits. In addition to winning the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2022 — the first Native American composer to be so honored — Chacon was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2023.

Aside from their unusual graphic design, his scores are full of sonic surprises. One (American Ledger No. 1) calls for the amplified whisper of a struck match, coins rattling around in tin cans, the piercing trill of a metal whistle, an actual ax splitting an actual log. At times Chacon hovers on the periphery of the barely audible; other times he threatens minor aural assault. But don’t fret about forgotten ear protection: think punk rock, or heavy metal, or the Lay Family Organ when Bradley Hunter Welch pulls out all the stops. This is loudness as love language.

Born in Fort Defiance, Navajo Nation, Chacon brings his ancestral culture and folkways to the Western classical and avant-garde traditions. He holds degrees in music composition from the University of New Mexico and the California Institute of the Arts, where he studied with Morton Subotnick, James Tenney and Wadada Leo Smith. Although Chacon is fluent in traditional Western music notation, he was frustrated by its constraints. One of his foundational musical memories was hearing his grandfather sing in Diné bizaad, the Navajo language of their ancestors, while they watched a football game on television; another formative experience was attending a John Cage recital with his piano teacher when he was in his early teens. Improvisational and aleatoric procedures made an impact on him long before he knew what to call them.

Inscription, Chacon’s first piece for full orchestra, draws from myriad compositional influences, reflecting experimental techniques and strategies that he has explored in smaller chamber ensemble settings. One such concept is microtonalism: the use of intervals smaller than a semitone, or half-step, which allows for subtle tones that elude the five lines and four spaces of the Western music staff. Chacon also incorporates his work as a visual artist, including experiments with timbral gestural drawing and illustration.

Although he lived to be 82 and produced an impressive quantity of music, Bruch never wrote anything that people love as much as his Violin Concerto No. 1, which he completed in 1866, when he was 28. After incorporating advice from the Austro-Hungarian violin virtuoso and composer Joseph Joachim, Bruch debuted the revised version, with Joachim as soloist, in 1868. It was an immediate hit.

Bruch suffered many financial hardships during his long career, and even his most enduring success was marred by rotten luck. As an impoverished young composer, he sold the publishing rights to his First Violin Concerto for a pittance in a one-off deal that didn’t allow him a share of future royalties. Even worse, his later compositions were nowhere near as popular. He was still irate about this injustice 20 years later. “Nothing compares to the laziness, stupidity and dullness of many German violinists,” he fumed in a letter to his publisher. “Every fortnight another one comes to me wanting to play the First Concerto; I have now become rude, and tell them: ‘I cannot listen to this concerto anymore — did I perhaps write just this one? Go away, and play the other Concertos, which are just as good, if not better.”

Few of those German violinists listened, and who can blame them? Today it remains among the few Bruch compositions that most listeners recognize.

By the end of World War I, Bruch was 80 and perilously poor. With the European economy in ruins, he had no way to collect royalties and no regular income. Although his terrible publishing deal meant that he couldn’t profit from the runaway success of his First Violin Concerto, he hoped to make some quick cash by selling his original copy of the score. He sent it to the concert pianists Rose and Ottilie Sutro, who were supposed to sell it for him in the United States. Instead, they bamboozled the desperate old man, who died on October 2, 1920, still waiting on his check. The sisters sent some worthless German money to Bruch’s family and refused to answer questions about the anonymous buyer who had supposedly purchased the score. In 1949 the swindling Sutros finally managed to sell it to the Standard Oil heiress Mary Flagler Cary, who ultimately bequeathed it, along with the rest of her papers, to the Pierpont Morgan Public Library in New York.

A Closer Listen

As Bruch was first to admit, the three-movement concerto is unconventionally structured. He even asked Joachim if he should call it a “Fantasia” instead. (The violinist assured him that “the designation concerto is completely apt.”) Starting with its Beethovenian opening gesture, a rolling timpani whisper, the Vorspiel (Prelude) thrillingly subverts sonata form. The solo violin lingers, flutters and soars like a lark ascending. The orchestra surges against it: an elemental exchange, like tide and moon. At the ultra-Romantic midpoint, the violin swoops up and down in wild chromatic abandon. But instead of moving on to the expected development section, the music circles back to the beginning, hushed and expectant.

Just like that, the prelude seeps into the Adagio, the concerto’s radiant core. It’s the most famous of the three movements, and no one who has heard it could wonder why. The melodies sound spontaneous as birdsong, essential as sunlight.

The finale hits the sweet spot between reckless and restrained. The orchestra trades off tunes with the solo violin, sometimes supplying thoughtful counterpoint, sometimes erupting into pyrotechnics. The soloist doles out Hungarian-spiced licks — Bruch’s stylistic nod to Joachim’s ethnic heritage — interspersed with copious, crowd-pleasing passagework.

The problem with canonical works — masterpieces, prized cultural artifacts, warhorses, whatever term you prefer for Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony — is that we stop listening when we think we get it. We reduce the irreducible to a trite slogan, something that fits on a bumper sticker. Unfortunately, Beethoven’s Fifth, like his Ninth, has acquired so many layers of meaning over the past 200 or so years that we risk missing out on its visceral pleasures. Because we have heard it so many times by now—at the concert hall, on The Simpsons, in countless commercial —it’s hard to imagine a time when that relentless four-plus-four motto didn’t enjoy permanent earworm status. It’s even more difficult to imagine hearing it in 1808, when Beethoven unleashed it on poor, unsuspecting Vienna. The shock of its radical simplicity was more subversive than punk rock. Beethoven’s Fifth will always be more than a symphony about struggle and triumph, all the things we feel compelled to make it mean. Listen to me when I tell you not to listen to me. Just listen.

Prodigious Feats

Beethoven worked on his Fifth Symphony intermittently for more than four years, between 1804 and 1808, a period of astonishing productivity. Starting in about 1799, when he was in his late 20s, he made the transition from keyboard virtuoso to major composer. By the time he was 38, he had completed six symphonies, a choral fantasy, four concertos, 11 piano sonatas, nine string quartets, an opera, a mass, a collection of overtures, a wide range of chamber music and various incidental pieces, all utterly transformative.

Creatively, he was working at a superhuman level, but everything else was grinding misery: worsening deafness, excruciating physical pain, a dreary parade of romantic rejections. Some evidence suggests that he may even have attempted suicide by self-starvation. But his subjective anguish didn’t turn him into a navel-gazing proto-Romantic. As biographer Jan Swafford explains, Beethoven wrote music for Romantics without being a Romantic: “He was not mainly concerned with ‘expressing himself’. As in all his music, even if there were echoes of his own life the goal was not autobiography but a larger human statement…. The Fifth proclaims every person’s capacity for heroism under the buffeting of life, a victory open to all humanity as individuals…. As he would put it one day: through suffering to joy.”

A Closer Listen

It all starts with that famous motto, the unforgettable ta-ta-ta-TAH, which, in the words of Beethoven’s notoriously unreliable first biographer, Anton Schindler, was intended to represent the knock of fate at the door. Whether Beethoven actually spelled it out that baldly is debatable. More significantly, Beethoven trusted his audiences to figure out the meaning of the motive without a program.

Movement by movement, the drama plays out in the tensions of rhythm and tonality. The primal figure, that propulsive sequence of three Gs and an E-flat, engenders everything. Beethoven’s sketchbooks show how much he struggled over the opening movement (simplicity is hard!). By simplifying the classical sonata-form paradigm perfected by Haydn and Mozart, Beethoven distilled the formula (exposition, development, recapitulation, coda) to a concentrated and potent substance.

In the transition to the recapitulation, horns emerge from a fog of drifting strings and winds. A melancholy oboe sings a brief descending cadenza, a small defiant act in the greater turbulence. This downward-swooping soliloquy foreshadows the lucid flow of the second movement. In a series of alternating double variations, the Andante con moto reconfigures the thematic material into expressions of tenderness and dread.

The third movement is technically a scherzo and trio (in meter, tempo, and form), but it’s far from a joke. As Richard Osborne wrote, “The pizzicato link to the passage on the drum takes us into a spectral, twilit world from which there seems to be no escape. Against this background the drum sounds its repeated low C, a note so laden with the feel of C minor at this point in the score that at each new hearing, all thoughts of a resolution are, to normal sense, more or less unthinkable folly.”

And then, after so much harmonic disruption, the C of C minor reveals itself as the C of C major in the radiant finale. Beethoven augmented the all-important brass with trombones, creating a novel coloration (if this wasn’t the first use of trombones in a symphony, it was surely among the earliest). Expanding the orchestral palette even further, Beethoven topped things off with a piccolo. As Swafford writes, “For those equipped to understand it, the gist would be clear enough in the notes. That story would be as direct as the rest of the symphony: a movement from darkness to light, from C minor to C major, from the battering of fate to joyous triumph.”

Coincidentally, the ta-ta-ta-TAH pattern spells out the letter “V” in Morse code, which inspired Allied soldiers during World War II to call the Fifth the “Victory” Symphony.