Shostakovich & Korngold

5 - 8 de enero de 2023

JAMES CONLON lleva a cabo

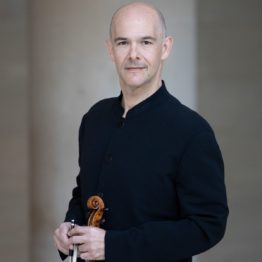

ALEXANDER KERR violín

SHOSTAKOVICH Obertura festiva

KORNGOLD Concierto para violín y orquesta en re mayor

SHOSTAKOVICH Sinfonía nº 5 en re menor

Este concierto incluye tres magníficas obras de compositores que buscan la redención.

Korngold escribió su lírico y cinematográfico Concierto para violín, que abarcaba tanto su educación vienesa como su estilo romántico pleno como compositor definitorio de la Edad de Oro de Hollywood. El concertino Alexander Kerr (Cátedra Michael L. Rosenberg) será el solista.

Escrita en sólo tres días a instancias de un director de la Orquesta del Teatro Bolshói, que debido a misteriosas maniobras políticas y chapuzas burocráticas necesitaba una nueva obra para celebrar la Revolución de Octubre, y el concierto era en tres días. El amigo de Shostakovich, Lev Lebedinsky, se sentó a su lado y comenzó a componer. Lebedinsky cuenta:

"La velocidad con la que escribía era realmente asombrosa. Además, cuando escribía música ligera era capaz de hablar, hacer chistes y componer simultáneamente, como el legendario Mozart. Se reía y reía, y mientras tanto se trabajaba y se escribía la música".

Durante el reinado de Stalin, Shostakovich pasó gran parte de su tiempo jugando al gato y al ratón con la policía cultural; siempre tratando de ampliar sus límites artísticos sin ofender a Stalin por parecer demasiado formalista.

El compositor Shostakovich ha recibido muchas críticas de los musicólogos occidentales por parecer que capitulaba ante los caprichos de Stalin y sus secuaces. En aquella época, las críticas suponían una amenaza para la vida, no sólo para la carrera, lo que explica que Shostakovich retuviera su exploratoria Cuarta Sinfonía (que se interpretará más adelante en la temporada) y compusiera en su lugar la Quinta para complacer al régimen.

Es interesante considerar cómo Shostakovich podría haber percibido el lugar del artista en el orden estalinista de las cosas cuando relata:

"Un artista cuyo retrato no se parecía al líder desapareció para siempre. Lo mismo ocurrió con el escritor que utilizó 'palabras crudas'. Nadie entró en discusiones estéticas con ellos ni les pidió explicaciones. Alguien vino a por ellos por la noche. Eso es todo. No fueron casos aislados, ni excepciones. Debe entenderlo".

"No importaba cómo reaccionaba el público ante tu obra o si le gustaba a los críticos. Todo eso no tenía importancia en el análisis final. Sólo había una cuestión de vida o muerte: ¿qué le pareció tu Op. al líder? Subrayo: vida o muerte, porque aquí estamos hablando de vida o muerte, literalmente, no figurativeamente. Eso es lo que debes entender".

"...Conlon ha asumido plenamente el manto del más consumado director musical que se encuentra actualmente en el podio de un teatro de ópera estadounidense".

Noticias de la Ópera

Notas del programa

por René Spencer Saller

Dmitri Shostakovich spent most of his career falling in and out of political favor with Joseph Stalin and the Soviet functionaries who did his bidding. One year the culture cops would be in raptures over his music, lavishing accolades, awards, and even, on one occasion, a country home on the composer; the next year, they would berate him for “decadent formalism” and other perceived crimes against Socialist Realism and deprive him of the opportunity to perform, publish, or record.

As if that weren’t punishment enough, Shostakovich had reason to fear for his life. He kept a packed suitcase by the door and often slept in the outer foyer to reduce the risk to his family in the event of a late-night raid. He wasn’t being paranoid. Countless friends and colleagues had disappeared in the dead of night to be executed or detained in penal camps, all for seemingly minor, even unintentional infractions.

But by 1954, when Shostakovich wrote his Obertura festiva, his main nemesis was dead, and he could relax somewhat. (Stalin died on March 5, 1953, the same day as Shostakovich’s fellow composer and countryman Sergei Prokofiev, also branded a decadent formalist.) Several commentators have suggested that the jubilant mood of the overture reflects Shostakovich’s joy over the dictator’s death, but this remains speculation.

What we do know comes courtesy of Shostakovich’s friend Lev Lebedinsky, who was visiting the composer at his home one autumn day in 1954, when Vassili Nebolsin, a conductor from the Bolshoi Theater Orchestra, showed up at his door with an urgent commission: The company needed a new work to commemorate the 37th anniversary of the October Revolution—for a concert that would take place in three (!) days.

Shostakovich rose to the challenge. Working swiftly and cheerfully, he managed to meet his impossible deadline. Before an hour had elapsed, he was handing over pages of the score to Nebolsin’s couriers, who conveyed them, ink barely dry, to the Bolshoi copyists entrusted with preparing the orchestral parts for performance.

“The speed with which he wrote was truly astounding,” Lebedinsky recounted. “Moreover, when he wrote light music he was able to talk, make jokes, and compose simultaneously, like the legendary Mozart. He laughed and chuckled, and in the meanwhile work was under way and the music was being written down.”

Shostakovich conducted a professional orchestra only once in his life, in 1962, at a concert devoted to his own music that was organized by the conductor and virtuosic cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, a good friend. To open the program, Shostakovich selected his Obertura festiva. Five years after his death, the piece became internationally famous as the signature theme of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.

Una escucha más atenta

Lebedinsky, who attended the dress rehearsals, described the Obertura festiva as “this brilliant, effervescent work, with its vivacious energy spilling over like uncorked champagne.” Shostakovich, for his part, used more prosaic language: “just a short work, festive or celebratory in spirit.”

The six-minute piece begins with a brass fanfare, which the composer borrowed from a song that he had originally written to mark his daughter Galina’s ninth birthday. (Eight years after his death, the birthday composition was appended to his Children’s Notebook, Op. 69, although he never considered it part of that cycle himself.) The clarinets announce a frisky motif, which is taken up by the other winds. The horns respond with a secondary theme—stately and ceremonial enough to provide contrast but not so serious as to seem ponderous. Throughout Shostakovich supplies electrifying rhythms, unexpected harmonies, pizzicato strings, and blindingly fast melodic runs. After the reprise of the fanfare motif, a propulsive coda brings the Obertura festiva to an incendiary close.

The son of a prominent Viennese music critic, Erich Wolfgang Korngold ranks among the greatest child prodigies in music history. His first ballet was professionally staged when he was only 13. By the time his opera Die tote Stadt received simultaneous premieres in Hamburg and Cologne, the 23-year-old was one of the most famous composers in Europe. But then disaster struck. His latest opera could not even be performed in Vienna because of the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938. As Korngold drily observed, “We thought of ourselves as Viennese; Hitler made us Jewish.”

Over the next seven years, the Nazis would murder an estimated six million Jews across German-occupied Europe, approximately two thirds of the European Jewish population. Given the brutal realities of the Holocaust, it’s no exaggeration to say that Korngold’s side job as a film composer likely saved his life. To make extra money, he had been collaborating with the director and impresario Max Reinhardt, another Viennese Jew. Reinhardt had hired Korngold to adapt the score of Mendelssohn’s incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, both stage and film versions. In 1938, after accepting a fortuitously timed commission to write the music for The Adventures of Robin Hood, Korngold moved to Hollywood for good; five years later, he became a U.S. citizen.

All told, he composed 18 original scores for feature films. Several were nominated for Academy Awards, and two won. Korngold chose to devote his final years to concert music, but he never regarded his film scores as inferior. “Never have I differentiated between my music for the films and that for the operas and concert pieces,” he maintained. “Just as I do for the operatic stage, I try to give the motion pictures dramatically melodious music, sonic development, and variation of the themes.”

From Triumph to Flop to Triumph

Korngold composed most of the material for his first and only violin concerto between 1937 and 1939, revising the work substantially in 1945, the year of its completion. He began the sketches with Bronislaw Huberman in mind for the solo part, but as the aging virtuoso’s technical skills began to deteriorate, Korngold consulted other violinists, including the one he eventually chose, his neighbor, Jascha Heifetz.

Beyond agreeing to debut it, Heifetz helped Korngold perfect the score, ensuring that the violin writing struck the right balance between lyricism and virtuosity. Korngold compared these two aspects of his concerto to the opera singer Enrico Caruso, known for his romantic intensity, and the legendary violin virtuoso and composer Niccolò Paganini, the epitome of the supernaturally endowed showman.

“In spite of the demand for virtuosity in the finale,” Korngold wrote, “the work with its many melodic and lyric episodes was contemplated more for a Caruso than for a Paganini. It is needless to say how delighted I am to have my concerto performed by Caruso and Paganini in one person: Jascha Heifetz.”

Korngold dedicated the concerto to Alma Mahler-Werfel, the widow of his early supporter and mentor Gustav Mahler.

On February 15, 1947, Vladimir Golschmann led the virtuoso Jascha Heifetz and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in the wildly successful premiere of Korngold’s Violin Concerto. The audience waxed ecstatic, giving the musicians what was, according to some accounts, the longest standing ovation ever recorded for any concerto performed by that orchestra. Korngold described his joy in a diary entry: “The reception of the Violin Concerto in St. Louis was triumphal…, a success just as in my best times in Vienna. One reviewer even predicted that my concerto would remain in the repertoire for as long as Mendelssohn’s. I do not need more than that!”

Unfortunately, the concerts in New York City didn’t go as well. Despite or possibly because of its popular appeal, the critics dismissed the concerto. Olin Downes of The New York Times called it a “Hollywood Concerto,” complaining that “the facility of the writing is matched by the mediocrity of the ideas.” Irving Kolodin, at the now-defunct New York Sun, quipped that the concerto was “more corn than gold,” a classic diss that will outlast all memory of Kolodin himself.

But musicians often have more sense than critics, and Heifetz remained loyal to the Violin Concerto. In 1953 he made a classic recording of the concerto with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. For decades he was virtually alone in performing Korngold’s Violin Concerto, but eventually other violinists fell under its spell.

Una escucha más atenta

Korngold’s choice of D major for the home key is somewhat obvious, given the genre. D major brings out the violin’s singing tone because the four strings of the instrument are tuned to G, D, A and E, and the open strings resonate brilliantly with the D string, producing a special radiance.

The solo violin opens the Moderato nobile with a piercingly sweet, ultra-hummable melody that the orchestra lovingly echoes. As in Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, Korngold’s concerto begins with the soloist’s voice, minus the typical orchestral introduction. The development section generates a mischievous riff that functions as a secondary theme. The mood is pensive and yearning, veering between rhapsodic and frenetic. Most of the music consists of material from his film scores for Another Dawn (1937) and Juarez (1939). Although the Moderato nobile is intensely lyrical, it gives the soloist ample space for bravura passagework and other technical challenges.

The central movement, marked Romance: Andante, is a shimmering, spellbound idyll. Xylophone, vibraphone, harp, and celesta radiate mystery and—as promised by the title—romance. After a brief introduction, the solo violin enters in the upper register, ardent and aching. The slow, plangent melody is mainly derived from the Academy Award–winning score for Anthony Adverse (1936)—specifically, the romantic theme representing the hero’s passionate but doomed love affair with an opera singer who bears his child but dumps him for Napoleon.

Recycled from the score for The Prince and the Pauper (1937), the delirious finale (Allegro assai vivace) is structured in theme-and-variations form, but thanks to Korngold’s bold instrumentation and scoring, the insistent, jiglike theme never grows monotonous. The Netflix hit Stranger Things used a representative snippet of this movement in a Season Four episode featuring the precocious homeschooled computer hacker Suzi and her many ungovernable siblings, who collude in an unlikely victory over their clueless dad and assorted evil forces.

In 1925, when Shostakovich wrote his Symphony No. 1 in F minor, he was only 18 years old. The talented St. Petersburg native had started piano lessons as a child with his conservatory-trained mother, advancing so rapidly that he was accepted to the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13. His First Symphony, submitted as a graduation thesis, quickly became an international sensation. Soon after its Leningrad debut, on May 12, 1926, the new symphony made the rounds of the major orchestras.

Rising from the Muddle

After a promising launch, Shostakovich’s career took a sudden nosedive. In 1936, around the time that the composer was preparing to debut his groundbreaking Fourth Symphony, Joseph Stalin attended a Moscow performance of Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtensk District—nearly two years after its successful premiere in Leningrad—and denounced it in an anonymous broadside titled “Muddle Instead of Music.” Condemned for its dissonant bourgeois degeneracy and other violations of Communist dogma, the opera disappeared from the repertoire for about 40 years.

By the mid-1930s, Socialist Realism was not only Russia’s dominant musical style; it was the only safe musical style. Composers who dared to explore avant-garde Western forms soon learned to expect the wrath of Stalin and his cultural watchdogs. Many Russian artists, composers, and patrons were executed, sent to gulags, or simply made to vanish. Concert music was expected to honor the proletariat and impart an unequivocally patriotic message. State-approved compositions typically incorporated folk songs and ended in a major key.

After getting slapped with the Lady Macbeth review, Shostakovich was justifiably terrified. For several months, convinced that further punishment was nigh, he slept in the stairwell outside his apartment to spare his family the trauma of witnessing his arrest. He withdrew his Fourth Symphony from performance. Over the next couple of years, he kept his head down, occupying himself with an arrangement of a Strauss operetta, some film scores, and various duties associated with his new position as conservatory professor. He would not share the Fourth with the public until 1961.

A Censor-Appeasing Proletariat Pleaser

Despite the Lady Macbeth misstep, Shostakovich was able to restore his good standing with his Soviet overseers, thanks in no small part to the proletariat-pleasing, censor-appeasing Fifth Symphony, which caused a sensation at its 1937 premiere. He even agreed to describe the D Minor Symphony as “a Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism.” By this point, Shostakovich understood exactly how to tiptoe around the government censors, although he sometimes felt compelled, whether out of bravery or sheer perverseness, to poke at them instead.

He began the Fifth Symphony on April 18, 1937, and finished it a mere three months later, on July 20. Evgeny Mravinsky led the Leningrad Philharmonic in the world premiere on November 21, 1937. The applause afterwards lasted longer than 30 minutes, causing Shostakovich’s friends to fret that it might provoke a backlash from the Soviet authorities. The composer was safe, though, at least for the time being.

Although audiences loved the Fifth, early reviews were uneven. Pravda slammed it, calling it “a farrago of chaotic, nonsensical sounds.” On the other hand, the state critics pronounced it “a work of such philosophical depth and emotional force [as] could only be created here in the USSR.”

Shostakovich described the Fifth as a response to human suffering: “I wanted to convey in the Symphony how, through a series of tragic conflicts of great turmoil, optimism asserts itself as a world view.”

Una escucha más atenta

In his program notes, Shostakovich described the Moderato as a “lengthy spiritual battle, crowned with victory,” which may explain the martial, menacing main theme. In this long and remarkably varied movement, Shostakovich juxtaposes a stark string motif with a more diffuse, melancholy secondary theme, derived from a Slavic folk song; this combination gives way to a violent, pell-mell march. A lustrous duet between solo flute and horn leads to a haunting, celesta-kissed coda, which resurrects the first theme.

The Allegretto functions as a brief scherzo, in contrast to the more serious surrounding movements. Crackling with a broad, often grotesque humor, the second movement displays a panoply of instrumental colors. A queasy waltz, pizzicato string counterpoint, and stuttering bassoons contribute to the circus-like atmosphere.

The Largo, the heart of the symphony, seemed to affect the audience at the premiere most deeply. Recognizing it as a Requiem, suffused with the liturgy of the Russian Orthodox Church, many listeners wept openly—never mind that public crying was a punishable offense under Stalin. Shostakovich achieved the radiant, enveloping sound by dividing the violins into three sections instead of the usual two, with the violas and cellos split into two sections. This setup allows for richer textural interest as well as complex counterpoint. Toward the end of the movement, a celesta and a pair of harps cast an especially entrancing spell. The brass instruments are entirely absent, perhaps because they dominate the finale.

The concluding Allegro non troppo brings back the martial idea explored in the opening Moderato, but now more joyously, with an almost ferocious dedication to fun. Toward the end, just before the rousing, timpani-pounding climax, Shostakovich quotes from one of his own unpublished songs, a setting of lines from Alexander Pushkin’s Rebirth: “And the waverings pass away/From my tormented soul/As a new and brighter day/Brings visions of pure gold.”

In Solomon Volkov’s controversial and highly contested Testimony, which purported to be Shostakovich’s memoir but was found to contain several inauthentic or fabricated quotations, Volkov ascribes to the composer the following description of his Fifth Symphony:

“Awaiting execution is a theme that has tormented me all my life. Many pages of my music are devoted to it…. I think it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created under threat, as in Boris Godunov. It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, ‘Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing,’ and you rise, shaky, and go marching off, muttering, ‘our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing.’ What kind of apotheosis is that? You have to be a complete oaf not to hear that.”

This statement would seem to contradict Shostakovich’s note from 1937 (which, to be fair, was written by a man whose life was at stake): “The theme of my symphony is the making of a man. I saw man with all his experiences as the center of the composition…. In the finale the tragically tense impulses of the earlier movements are resolved in optimism and the joy of living.”