Beethoven and Mozart

November 22 – 24, 2024

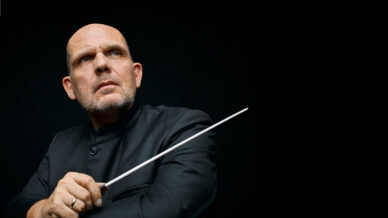

FABIO LUISI conducts

FRANCESCA DEGO violin

BEETHOVEN Violin Concerto in D Major

MOZART Symphony No. 41, “Jupiter”

Two favorites of classical music await you at this concert, masterfully led by Music Director Fabio Luisi. Fellow-Italian, violinist Francesca Dego, joins him and the DSO for Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, a magisterial creation of dramatic impact some violinists have dubbed their “Mount Everest.” Scaling this musical mountain lets performers reveal their emotional depth in lyrical passages and their technical mastery in high-voltage fireworks. Mozart’s regal “Jupiter” Symphony, aptly named for the king of the gods, with drums and trumpets lending a stately feel, set a crown upon the composer’s symphonic output.

Join us for a special pre-concert talk with Assistant Conductor Shira Samuels-Shragg! The talks will take place from Horchow Hall starting at 6:30pm on Friday and Saturday and 2:00pm on Sunday.

Program Notes

by René Spencer Saller

Starting in about 1799, when he was in his late 20s, Beethoven began transitioning from keyboard virtuoso to major composer. Within a decade, he completed six symphonies, a choral fantasy, four concertos, 11 piano sonatas, nine string quartets, an opera, a mass, a collection of overtures, a wide range of chamber music and various incidental pieces.

Creatively, he was working at a superhuman level, but everything else in his life was grinding misery. Some evidence suggests that he may have attempted suicide by self-starvation. But his personal agony didn’t turn him into a navel-gazing proto-Romantic. His middle-period compositions reveal a maturing harmonic language and an increasingly personal, intuitive, subjective mode of expression.

Thanks to his “Heiligenstadt Testament” from 1802—an unsent suicide note to his family that was discovered after his death—we know that his worsening deafness was his greatest misery and shame. Describing his urge to end his own life, the 31-year-old composer wrote, “Only Art, only art held me back. Ah, it seemed impossible to me that I should leave the world before I had produced all that I felt I might, and so I spared this wretched life.”

In the decades to come, Beethoven stuck to what he called his “new path,” despite enduring almost complete hearing loss, excruciating digestive ailments, a possible lupus-like condition and a succession of stinging romantic rejections. These would be creatively productive years for him, wretchedness be damned.

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major—his first and only violin concerto—was seldom performed during his lifetime. Luckily, 17 years after the composer’s death, it was rescued from undeserved obscurity by Joseph Joachim and Felix Mendelssohn, who, as soloist and conductor, respectively, performed the concerto so brilliantly that it quickly became a staple of the concert repertoire, as it remains today.

Beethoven wrote the D Major Concerto during the most productive period of his life. For years he had known that he was going deaf, a crisis that pushed him deeper into his work and invested it with a new expressive urgency. His so-called middle period (from approximately 1804 to 1812) is lousy with masterpieces. In 1806 alone, he finished the Leonore Overture No. 3, the Fourth Piano Concerto, the Fourth Symphony, 32 Variations on an Original Theme in C Minor and the three Razumovsky Quartets. He also accepted a commission from the superstar violinist Franz Clement, whom he had known since 1794, when Clement was a 13-year-old prodigy. The Violin Concerto is dedicated to the virtuoso, and its first performance took place at a benefit concert for him.

The premiere, in December 1806, was a disappointment. The audience cheered Clement but seemed puzzled by Beethoven’s music. According to some contemporary accounts, Clement hammed it up by interpolating a splashy composition of his own, played on one string of his upside-down violin. Such show-biz shenanigans were common in the early 19th century and probably not the reason that the concerto flopped. It’s more likely that Beethoven’s chronic procrastination resulted in a substandard, under-rehearsed performance by the soloist and the orchestra—Beethoven was scribbling out revisions mere days before the scheduled concert. But even more daunting were the many liberties that he took with sonata-allegro form. Ridiculing the ruptures in continuity and the “needless repetition of a few commonplace passages,” an early critic darkly predicted that “if Beethoven will pursue his present path, he and the public will come to no good end.”

A Closer Listen

Right away, the concerto announces its consummate weirdness. It begins, unlike any concerto before it, with five soft taps on the timpani. Then the woodwinds introduce a serene melody, only to be interrupted by the violins’ strange mimicry of the timpani’s opening knocks. This rhythmic motif—sometimes four beats, sometimes five—recurs throughout the symphony, in many disguises, informing every melody and inspiring dozens of variations. After a lengthy orchestral buildup, the solo violin finally enters, playing a melody that has previously appeared only in tantalizing snippets. Its beauty aside, this solo is no show-off’s showpiece. Beethoven makes it clear that the soloist and orchestra are equal partners, with a shared goal.

In the lyrical Larghetto, serene strings float in a shimmering pool of G major. The theme surfaces, sung by muted strings, and the soloist spins out a series of increasingly complex variations.

After a brief cadenza, the last movement—played without pause after the central Larghetto—reveals itself as an unorthodox rondo. As it builds to a close, the finale erupts in a flurry of robust and virtuosic passages.

Like Olivier Messiaen, Ottorino Respighi, John Luther Adams and countless other great composers, Mozart was fascinated by birdsong. For about three years, as Lyanda Lynn Haupt and others have documented, Mozart kept a pet starling, delighted by the creature’s gift for mimicry. In an expense notebook entry for May 27, 1784, Mozart noted that he’d spent 34 kreuzer to buy the Vogelstar (starling), and then he transcribed a version of the opening theme from the finale of his recently finished Piano Concerto No. 17, as sung by the starling. The bird appears to have adjusted the rhythm at one point and switched a G-sharp for a G; underneath his notated bird rendition, Mozart scrawled, “That was beautiful!”

When the starling died on June 4, 1787, Mozart buried his pet in the backyard and wrote a brief but heartfelt elegy: “A little fool lies here/Whom I held dear.”

No one knows exactly who came up with the “Jupiter” nickname for Mozart’s final symphony, but it wasn’t the composer himself. At any rate, the Roman god is a decent avatar for Symphony No. 41. Who else could represent Mozart’s magisterial four-movement symphony in C major but the ruler of thunder, the king of the gods, the divine diplomat?

Miraculously, Mozart managed to complete his last three symphonies in June, July and August of 1788. The recent publication of Haydn’s “Paris” symphonies—three of which are in the same keys that Mozart chose for Symphonies 39 through 41—might have given him the idea. Mostly, though, the cash-strapped composer needed some new material to perform, and he hoped that a fresh batch of symphonies might entice potential clients in London.

Obviously, Mozart had no idea that he’d be dead in three years, or that he’d never write Symphony No. 42. That inconvenient detail doesn’t stop people from interpreting the final symphony as some kind of conscious, career-culminating farewell. But Mozart was far more interested in musical juxtaposition than in self-expression, and Symphony 41 is in many ways an opposing response to its immediate predecessor, in G minor. The English musicologist Julian Rushton called them “twins of opposite character.”

A Closer Listen

As with the Figaro overture, the Allegro vivace immediately announces its intention: to mix things up. Martial pomp collides with lyrical sweetness. Violent storms subside in opera buffa whimsy. Mozart quotes one of his own recent arias, hilariously out of context, and subverts fusty high art–versus–low art conventions by subjecting the unassuming little ditty to some serious counterpoint.

In the Andante cantabile, low strings caress a dulcet clarinet motive, while the violins croon a sumptuous countermelody. Richly expressive, with long singing lines, the slow movement has the quality of an aria (the tempo indication means “songlike and flowing”). Next, a hint of the contrapuntal grandeur to come as a graceful minuet weaves together interlocking melodies based on a theme from the first movement.

The finale, marked Molto allegro, starts with a four-note motif that Mozart (and others) had used before, but it’s only a means to an end: even more extreme counterpoint. Here Mozart combines conventional Classical sonata form with fugue, a high Baroque procedure that fascinated him; he pored over (and occasionally filched) similar fugato-style passages in scores by Michael and Joseph Haydn. The monumental coda melds together five distinct motifs, the primary one derived from the earlier four-note plainchant melody.