Mozart & Prokofiev

April 28 – May 1, 2022

LEONIDAS KAVAKOS conducts

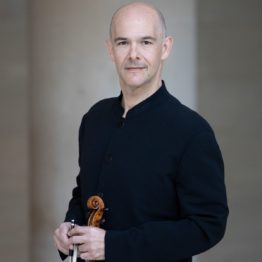

ALEXANDER KERR violin

MEREDITH KUFCHAK viola

MOZART Sinfonia Concertante for Violin and Viola, K. 364

PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 6

At only 23 years old, Mozart composed his warm and witty Sinfonia Concertante, a clever combination of symphony and concerto, to display the exceptional skills of the string players in the Mannheim Orchestra.

Prokofiev’s Sixth Symphony, an extremely powerful and moving work, depicts the suffering and loss that Russia experienced after World War II.

“Now we are rejoicing in our great victory, but each of us has wounds which cannot be healed. One man’s loved ones have perished; another has lost his health this must not be forgotten…The first movement is of an agitated character, at times lyrical, at times austere; the second movement is brighter and more songful; the finale, rapid and in a major key, is close in character to my Fifth Symphony, save for reminiscences of the austere passages in the first movement.”

– Sergei Prokofiev

For information on our COVID-19 safety protocols, please visit here.

Program Notes

by René Spencer Saller

Although we tend to think of Mozart as a keyboard virtuoso, he was also a first-rate violist and violinist. His father, Leopold, who published A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing the same year that Wolfgang was born, encouraged him in a letter: “You are not quite aware yourself of what an excellent violinist you are, when you gather up all your strength and play with self-confidence, verve, and fire.”

Others apparently agreed. The younger Mozart was appointed concertmaster of the Salzburg court orchestra at age 13, although he wasn’t paid for the first three years on the job. As concertmaster, he composed a total of five violin concertos, the first in 1773, when he was 17, and the rest two years later. He wrote these concertos for himself to perform, but other violinists—the few who were good enough, anyway—began playing them, too. His employer, Archbishop Hieronymous Colloredo, an amateur violinist himself, replaced Mozart with another concertmaster in 1777, but this choice had more to do with Mozart’s personality than with his abilities.

Mozart in Paris

Mozart first visited Paris at age seven, when Leopold took him and his prodigiously gifted older sister, Nannerl, on a European tour that lasted three and a half years. For Mozart’s second Paris sojourn, Leopold stayed in Salzburg and Wolfgang traveled with his mother, Anna Maria, as chaperone. But first they lingered for months in Mannheim, where the 21-year-old composer enjoyed performances by the best orchestra in Europe and fell in love with Aloysia Weber, his future sister-in-law. Leopold, appalled by this development, sternly put Wolfgang back on task: to secure a post at Versailles. Mother and son obeyed his orders, arriving in Paris in late March 1778.

“Be guided by the French taste,” Leopold recommended in a letter. “If you can only win applause and be well paid, let the devil take the rest.” Mozart complied. Despite an abysmal rehearsal the day before, his Symphony No. 31, “Paris,” went over well at its premiere that June. But less than a month later, his 57-year-old mother sickened and died. Mozart broke the awful news to his father by letter. In September he headed back to Salzburg, grieving and discouraged.

About a year later, in the summer or fall of 1779, when he seems to have written the Sinfonia Concertante, he was still stuck in Salzburg, longing to escape his hometown and Archbishop Colloredo’s clutches. His dream was to establish himself as a composer in Vienna, capital of Austria and epicenter of German-language opera, but in the meantime he meant to hone his skills as a composer of instrumental music.

Origins and Catalysts

We know next to nothing about the early performance history of Sinfonia Concertante, forcing annotators to speculate and choose among competing theories. It’s tempting to imagine Mozart, who preferred playing the deeper-voiced viola to the diva violin, assuming solo viola duties, with Leopold or the Salzburg court concertmaster, Antonio Brunetti, playing solo violin, but no evidence exists to support these or any other scenarios. The original copy of the score is lost, and the surviving manuscript fragments provide no clues about the date or first performance. The current edition of the work is based on the first published edition, which appeared a full decade after Mozart’s death. The surviving fragments indicate that Mozart wrote all the cadenzas himself; whether Brunetti or another violinist improvised or substituted his own cadenzas at the premiere remains unknown.

The Sinfonia Concertante, like the other music that Mozart wrote during this period, incorporates stylistic influences (including Italian opera) that he picked up during his extensive travels. In Paris and Mannheim, the multiple concerto, or sinfonia concertante, was all the rage, and Mozart took the opportunity to practice and adapt everything he learned from his foreign colleagues. In addition to the Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola, Mozart also composed a sinfonia concertante for four wind instruments and a concerto for flute and harp.

Focused on his own creative achievements at the expense of his duties as court organist, Mozart angered the Archbishop, who fired him. Suddenly free of court constrictions, as well as his bossy father’s direct control, Mozart left Salzburg and pursued his long-deferred dream of being a freelance composer in Vienna. Vienna would be his home for the rest of his short, brilliant life.

First Among Equals

Among the many extraordinary features of the Sinfonia Concertante is the absolute parity that Mozart grants his two lead instruments. He put the unjustly maligned viola—the original “second fiddle” —on equal footing with the violin, the string section’s usual prima donna. He did this partly by assigning some of his most sublime melodies to the viola, and partly by transposing the viola part to a slightly lower key (down a half-step, to D major). This peculiarity forces the violist to tune the instrument higher to match the key in which the other instruments are all playing, E-flat. In other words, by notating the solo viola part in D major, Mozart has the violist playing on open strings, which, combined with the higher tuning, confers a special ringing, resonant quality that the violin, playing in the home key and using the conventional tuning, can’t overshadow.

Even though the Sinfonia Concertante is now almost universally acknowledged as a cultural treasure, critics were underwhelmed by its U.S. premiere. A critic from The New York Times was especially scathing (not to mention obtuse): “On the whole we would prefer death to a repetition of this production. The wearisome scale passages on the little fiddle, repeated ad nauseam on the bigger one, were simply maddening.”

A Closer Listen

Aside from the solo viola and violin, Mozart calls for the usual strings, plus a pair each of oboes and French horns. Despite the relatively modest instrumentation, Mozart creates depth and interest by dividing the three instrumental groups (strings, oboes, horns) into smaller chamber-music groupings: the essence of the concertante concept, wherein instruments exchange lead and supporting roles.

The first movement, marked Allegro maestoso, begins with a premier coup d’archet (first stroke of the bow), a loud tutti opening gesture that was all the rage in fashionable Paris. “What a fuss these boors make of this! What the devil!” Mozart grumbled in a letter, referring to the trendy salvo. “I can’t see any difference—they all begin together—just as they do elsewhere. It’s a joke.”

After an ebullient orchestral introduction, the two solo instruments and the orchestra all supply a profusion of variations, each idea more ingenious and high-spirited than the next. At least two of the most exquisite solos go to the viola, but the most sublime moments happen when the two lead instruments play together, whether in unison or counterpoint. Joined, they sound most fully themselves.

The central movement, cast in moody C minor (an unusual choice for Mozart), boasts music so complex and bittersweet that it practically begs for an autobiographical explanation, never mind that Mozart ranks among the least autobiographically inclined composers in the entire Western canon. The grave and graceful Andante has a faintly antiquated, Bachian grandeur, a poignant quality that contrasts with the cheerful abundance of the opening movement. This distinctly elegiac mood, carried by the twilit viola, has prompted some biographers to suggest that Mozart must have been mourning his mother, whose death stained his memories of Mannheim and Paris.

The fast-paced finale plunges giddily into a dance-based rondo, returning to the home key and shrugging off the blues of the preceding Andante.

Prokofiev’s Sixth Symphony is a provocative, intensely original post–World War II effort that effectively destroyed his career. Denounced by Stalinist watchdogs as a “decadent formalist” who embraced “innovation for innovation’s sake,” the Russian composer spent the last six years of his life disgraced and demoralized. Although the Sixth rankled the enforcers of Socialist Realism, contemporary listeners savor the work’s bittersweet complexities. As Prokofiev understood all too well, every triumph contains a tragedy.

From Epic to Elegy

After the Revolution of 1917, Prokofiev spent more than a decade shuttling between France, England, the United States, and Germany. In the mid-1930s, the homesick composer returned to his native Russia, where he was embraced as a prodigal son. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, he turned his attention to patriotic projects, including a monumental opera based on Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Purely on a personal level, the war years were tumultuous. Two weeks after the successful premiere of his Fifth Symphony, his chronic high blood pressure caused him to faint and tumble down a flight of stairs, resulting in a serious concussion from which he never fully recovered. He also left his wife, Lina, the mother of his two sons, for the much younger Mira Mendelssohn, the librettist for War and Peace.

Prokofiev described his Fifth Symphony, from 1944, as “the culmination of a long period of my creative life.” Epic in scope and emotionally cathartic, it won the prestigious Stalin Prize. A few years later, he completed his Symphony No. 6 in E-flat minor, which was decidedly darker and weirder than its predecessor. “Now we are rejoicing in our great victory, but each of us has wounds that cannot be healed,” the composer cryptically explained. “One has lost those dear to him; another has lost his health. These must not be forgotten.”

If the Fifth felt triumphant, the Sixth skewed tragic. Its elegiac quality and other risky breaches of Socialist realism were duly noted by Andrey Zhdanov, Stalin’s powerful proxy. The Union of Composers denounced Prokofiev as a “decadent formalist,” and several of his titles were banned from performance. But even those works that escaped formal censure were unofficially blacklisted, and his health deteriorated as his debts mounted. After suffering what was probably a cerebral hemorrhage, Prokofiev died on March 5, 1953, just a month shy of his 62nd birthday. Ironically, Stalin died on the same day: his lavish funeral, attended by hundreds of thousands of mourners, contrasted sharply with the composer’s spartan service.

A Closer Listen

Prokofiev’s Sixth (and second to last) Symphony comprises three movements instead of the standard four. An average performance lasts about 45 minutes.

While putting the finishing touches on the orchestration, the composer wrote a brief summary: “The first movement is of an agitated character, at times lyrical, at times austere; the second movement, Largo, is brighter and more songful; the finale, rapid and in a major key, is close in character to my Fifth Symphony, save for reminders of the austere passages in the first movement.”

The first movement begins with a concise introduction and then launches into its restless first theme, in 6/8 meter. Dusky, almost funereal oboes croon the contrasting second theme. The central Largo pits an anguished, sporadically strident motif against a graceful, cello-driven melody before closing with melancholy oboe and muted trumpet. The Vivace pairs a rustic and rollicking violin tune with an agile, playfully virtuosic workout for solo bassoon. In the coda, Prokofiev briefly conjures up the sorrowful mood of the first movement only to dispel the gloom in the rousing final measures.