Sibelius’ Symphony No. 3

April 3 – 6, 2025

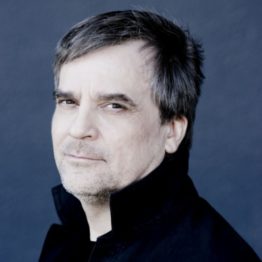

JOHN STORGÅRDS conducts, violin

EMILY LEVIN harp

BEETHOVEN Romance No. 2 for Violin and Orchestra

HENRIETTE RENIÉ Concerto for Harp and Orchestra

KEITH JARRETT Elegy for Violin and String Orchestra

SIBELIUS Symphony No. 3

Principal Harp Emily Levin is front and center for Henriette Renié’s gorgeous Concerto. Widely recognized for his dual career, John Storgårds both plays and conducts Beethoven’s composition of poignant lyricism and songlike eloquence as well as Keith Jarrett’s Elegy, which pushes the boundaries of what we think of as “classical.” In Sibelius’ Third Symphony, listen for his new approach to symphonic writing — “the crystallization of ideas from chaos,” he calls it, where fragments of melodies slowly begin to coalesce as the music proceeds, gathering energy and ending in a glorious C-Major chord.

Join us for a special pre-concert talk with Assistant Conductor Shira Samuels-Shragg (Marena & Roger Gault Chair)! The talks will take place from Horchow Hall starting at 6:30pm on Thursday and Friday and 2:00pm on Sunday.

Emily Levin

Principal Harp

Elsa von Seggern Chair

You may also be interested in

Program Notes

by René Spencer Saller

Beethoven wrote Romance No. 2 for Violin and Orchestra in 1798, a heady time for the wigless hotshot, who had relocated to Vienna from unfashionable Bonn about six years earlier. Now a coveted guest in the capital’s most exclusive salons, the 28-year-old virtuoso routinely slayed anyone foolish enough to challenge him to a piano duel. His bad-boy panache and superhuman passagework endeared him to well-born ladies, who encouraged his flirtation, despite his lack of a title or family money. He also played violin and viola more than capably, which accounts for his supple, idiomatic writing for the stringed instruments. Back in his native Bonn, he had played viola in the opera and chapel orchestras. In Vienna, the musical capital of the German speaking world, he could collaborate with some of the finest players alive.

These were Beethoven’s glory days, but disaster loomed: he was beginning to experience early symptoms of deafness, a roaring static that swallowed up all other sound. He didn’t yet know that his hearing loss was irreversible, incurable and worsening, but he knew enough to be terrified. Life without music was meaningless. In 1802 he expressed his suicidal thoughts in an unsent letter to his brothers that was discovered only after his death, more than two decades later. In this letter, the so-called Heiligenstadt Testament, he vowed to endure his misery for the sake of his art, his sacred mission.

A Closer Listen

If the young Beethoven was still formulating a distinctive style, his voice is unmistakable. The main hook keeps finding new ways to ensnare us even after the countless repetitions required by the rondo form. The harmonies and shifting instrumentation change the way we hear the them —more sunlight here, more shadows there—but for the most part Beethoven suspends us in the golden hour and lets us linger there.

From the opening bars the aria-like main tune and lilting dotted rhythms announce their Mozartean mandate: charm suffused with mystery, and vice versa. Beethoven marked the tempo Adagio cantabile—slow and singing—and the Romance really does sound like an instrumental outtake from a long-lost Mozart opera. It leaves us grateful but not quite sated, basking in the remembered light.

Unless you are a harpist, you may not know the name Henriette Renié. As a small child, the native Parisian played piano, but she switched to harp after hearing a leading virtuoso, Alphonse Hasselmans, perform in Nice. Although little Henriette had never touched the instrument, she predicted that Hasselmans would teach her someday. She began playing as soon as her parents brought her a harp, at age eight. Because her legs were still too short to reach the pedals, her father (a singer who had studied with Rossini) devised special extensions for her. At 10 she enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire, under Hasselmans, and won second prize in harp performance. She would have won first prize if the popular vote had carried, but the director of the Conservatoire intervened to keep her from being designated a “professional” too early. A year later, when she was 11, she won first prize and kept it this time. After graduating from the Conservatoire at 13, she went on to win all the major prizes, remaining in high demand as a performer and teacher. She kept her original compositions under wraps for years and focused on concertizing, making her public solo-recital debut at 15.

Perhaps in part because of her gender and her devout Catholicism, Renié wasn’t appointed successor to Hasselmans, her former mentor and (sometime frenemy) at the Conservatoire, but she gave lessons, often at no charge, and managed to support her own family as well as that of a former student. She started her own international competition and organized charity concerts to raise funds for impoverished musicians during World War I. In the 1920s she made several recordings until physical exhaustion and other ailments limited her ability to perform. During the Second World War she worked on her magnum opus, the two-volume Complete Harp Method, and continued teaching and giving occasional concerts, despite worsening health. She died in March, 1956, a few months after her last concert.

A Closer Listen

Renié began the Concerto in C Minor in 1894 and completed it in 1901. Set in four movements, it’s one of the most technically challenging works in the harp repertoire, bursting with dramatic contrasts and polyphonic intrigue. She dedicated it to Hasselmans, the harpist who first inspired her.

After reviewing the score, the composer-conductor Camille Chevillard was so impressed that he booked Renié for a series of concerts, which were not only warmly received but also enormously influential. These performances marked the first time that a harp was featured as a solo instrument with orchestral accompaniment. Thanks to Renié’s technical and interpretive brilliance, as well as the widespread appeal of her Harp Concerto, Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel and other major composers began writing major works for the instrument.

Born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, to a mother of Slovenian descent and a mostly German father, Jarrett ranks among the most distinctive — and commercially successful — pianists of all time. Very early in his career he collaborated with jazz legends such as Art Blakey, Charles Lloyd and Miles Davis; before he turned 30, he was one of the world’s top solo pianists, as well as the leader of diverse ensembles. His 1975 recording of live improvisations, The Köln Concert, ranks as the best-selling piano recording in history.

Jarrett has always defied category and catechism, a killer improviser who could riff on a Bach fugue as easily as he could vamp over a walking-blues progression or rework a jazz standard. Although piano is his primary instrument, he is also proficient on harpsichord, clavichord, organ, soprano saxophone and drums. He is much better known as a jazz artist, but he has been composing and recording classical music since the early 1970s. In addition to his own compositions, he has recorded interpretations and transcriptions of works by Bach, Handel, Shostakovich and Arvo Pärt. Elegy for Violin and String Orchestra appears on his 1993 collection of original compositions, Bridge of Light.

Jarrett received the Léonie Sonning Music Prize in 2003, becoming only the second jazz musician ever to win, after Miles Davis. In 2018 he suffered two strokes that left him partially paralyzed and unable to perform.

The Composer Speaks

“Music programs are often rife with explanatory notes concerning the technical details of the pieces. This distracts us from entering the state of ‘listening’ and, instead, makes us more likely to live in our head than in our heart. We seem more concerned with whether the program notes make sense than whether we can be touched by the sounds themselves.

“Elegy for Violin was written for my maternal grandmother, who was Hungarian and loved music.

[…]

“Actually, all of [the works on the album Bridge of Light] are born of a desire to praise and contemplate rather than a desire to ‘make’ or ‘show’ or ‘demonstrate’ something unique. They are, in a certain way, prayers that beauty may remain perceptible despite fashions, intellect, analysis, progress, technology, distractions, ‘burning issues’ of the day, the un-hipness of belief or faith, concert programming and the unnatural ‘scene’ of ‘art’, the market, lifestyles, etc., etc., etc. I am not attempting to be ‘clever’ in these pieces (or in these notes), I am not attempting to be a composer. I am trying to reveal a state I think is missing in today’s world (except, perhaps, in private): a certain state of surrender: surrender to an ongoing harmony in the universe that exists with or without us. Let us let it in.” —Keith Jarrett

One hallmark of the Sibelian style is the affinity for brief, almost fragmentary motifs that cunningly connect and cohere in the development section, only to shatter without notice. Describing his compositional method, Sibelius wrote, “It is as though the Almighty had thrown the pieces of a mosaic down from the floor of heaven and told me to put them together.” His Second Symphony, an immediate hit in his native Finland, was hailed as a “Symphony of Independence,” a defiant rebuke to Tsarist Russia in response to recent sanctions. Sibelius completed it in 1902, just two years after the patriotic anthem Finlandia, and his political convictions were well known. Several of his works had been censured by the authorities for inciting rebellion.

Three years later, as he struggled with his worsening alcoholism and the stringent standards that he had imposed on his unfinished Third Symphony, Sibelius found himself at a creative crossroads. “This is the crucial hour,” he wrote his wife, Aino, “the last chance to make something of myself and achieve great things.” He conducted the Helsinki Philharmonic in the first performance of the Third on September 25, 1907.

Symphony No. 3 represents one possible path forward, beyond nationalism to something profoundly personal and therefore universal. As with so many groundbreaking achievements, it baffled or bored most of his contemporaries, who felt let down by its relatively restrained instrumentation, its brevity, and its overall lack of expressive indulgence. As he confessed in a letter, “After hearing my Third Symphony, Rimsky-Korsakov shook his head and said: ‘Why don’t you do it the usual way; you will see that the audience can neither follow nor understand this.’” Later Sibelius would call the Third a “relapse,” a nostalgic, neoclassical backward glance.

A Closer Listen

Of all the keys, cheerful, reliable C major ranks as the real workhorse, the first scale and chord in our piano workbooks, a cleansing, restore-to-factory-settings signature that leaves us refreshed and ready for future harmonic mischief. If you were trained in the Western Classical tradition, as Sibelius was, C major feels like home. But the musical home Sibelius creates for Symphony No 3 is more David Lynch than Thomas Kinkade. Sibelius deconstructs C Major until he compels us to hear the key anew, in all of its sovereign glory.

The opening Allegro moderato marshals dramatically building cellos and basses, which create suspense and melodic interest as the mood shifts from vaguely ominous to downright festive. Set in dreamy, slightly destabilizing 6/4, the folk-inflected central movement is marked Andantino con moto, quasi allegretto, which means “a little faster than walking pace with movement, almost moderately fast.” Despite the lulling tempo — Sibelius uses hemiola, a rhythmic device that staggers sets of two beats against three — the nocturne-like vibe prevails, casting wistful shadows over the lustrous surface of the tunes. He also found a way to repurpose some material from an unfinished tone poem for soprano, Luonnotar. Listen for the chorale-like passage, which one of the composer’s friends described as a kind of “child’s prayer.”

Sibelius marked the last movement Moderato – allegro ma non tanto. He described this concise scherzo-finale twofer as “the crystallization of thought from chaos.”